Ancient Egyptian art was generally very formal, and presented an idealised version of the subject matter which often encompassed many layers of meaning. When depicting people, traditional art stuck closely to strict guidelines and depicted people in formal poses. Their image was idealised, but retained some of their subject’s facial characteristics. For example, Ramesses II can generally be recognised by his cute little nose.

Towards the end of the reign of Amenhotep III and throughout the reign of his son Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV), a new more flowing art form evolved. While it is often described as “naturalistic” it remains highly stylised in its portrayal of the human figure.

Akhenaten broke the mould in this respect and was depicted with a strangely elongated skull, wide hips, spindly legs, pendulous breasts, and a rounded belly. Akhenaten was not the only person to be depicted with a peculiar bone structure. Nefertiti and the princesses often emulate the elongated skull, while Bek, the Chief Sculptor and Master of Works, is depicted with pendulous breasts and a pronounced stomach. Bek states on a stele that he was taught by the king and instructed to represent what he saw, supporting the suggestion that Akhenaten did have an androgynous figure. However, Bek may have been referring to the glorious depictions of nature and family life and not specifically to Akhenaten’s form.

However, even within the Armarna period there were three recognisable phases during which the King and his family were depicted according to slightly differing artistic conventions. At the beginning of his reign, the king was depicted with a standard body shape. It is possible that he had not yet had a chance to develop the artistic form associated with the period, but it is also suggested that the depictions reflect reality before the disease began to affect the king. Then, under chief sculptor Bek, the idiosyncratic form associated with the King developed. He was depicted with feminine curves, heavy thighs and belly, half-closed eyes, full lips, and a long face and neck. Finally, towards the end of Akhenaten’s reign the chief sculptor Thutmose (or Djhutmose) took over from Bek and Akhenaten was depicted with a more normal shape, but still with an elongated skull.

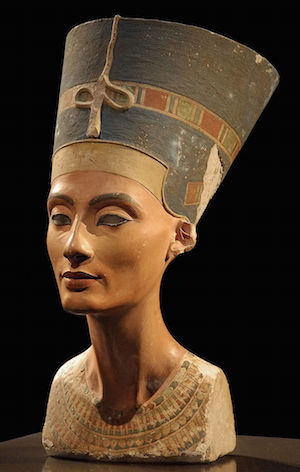

Thuthmose created some of the more beautiful representations of the family, including the famous bust of Nefertiti. While Nefertiti was often depicted with very similar facial features to her husband during Bek’s period, under Thuthmose her features were distinct and individual.

It remains unclear whether the idiosyncratic form was stylistic or realistic, but the mummies of both Smenkhare and Tutankhamun displayed a slightly elongated skull suggesting that the more abnormal depictions may have simply been an exaggeration.

During the reign of Amenhotep III (Akhenaten’s father) artists began to depict nature in all its glory in a naturalistic way not common to traditional ancient Egyptian art. This art form was also apparent during the reign of Akhenaten, as his worship of the sun disc included a reverence for the natural world. The depictions of nature from this period are among the most beautiful works of art recovered from Ancient Egypt.

The subject matter of royal art also changed. In addition to the formal scenes of the king worshipping, normal day-to-day activities are given prominence. There are a number of beautiful depictions of Akhenaten and Nefertiti playing with their daughters beneath the rays of the Aten. The beauties of nature are also prominent in royal art. Traditional art reflects a belief in the eternal, while Armarna art existed more in the moment and reveled in the glorious world created and governed by the all powerful sun.

Architecture

The proportions of the Aten Temple he built at Karnak are exaggerated and unconventional, methods of construction also changed. Smaller blocks of stone set in a strong mortar replaced the huge monumental blocks used by Akhenaten’s predecessors. It is quite possible that Akhenaten used art as a way to emphasize his differences from his predecessors, as when he moved to Akhetaten (Armarna) the art became less exaggerated. Official inscriptions also changed significantly, moving away from the old-fashioned traditional language to a less formal spoken style.

Akhenaten had a royal tomb built near his new city. Some suggest that the tomb was never used despite the discovery of smashed fragments of sarcophagus and canopic jars, and ushabtis found in the city and the tomb. In any case, it seems his body was moved some time after burial, but no one knows what happened to it. Some suggest his detractors exhumed him and destroyed his mummy, while others argue that his followers reburied him in the Valley of the Kings. It has even been suggested that his was the mummy buried in tomb KV55, although the body would seem to be too young.

Bibliography

- Dijk, Jacobus Van (2000) “The Amarna Period and the later New Kingdom”, in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt Ed I. Shaw

- Kemp, Barry (2015) The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Amarna and its people

- Malek, Jaromir (1999) Egyptian Art

- Robins, Gay (2008) The art of Ancient Egypt

- Tyldesley, Joyce (1998) Nefertiti

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000) The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt