Amenhotep III (Amenophis III) was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt. He ruled Egypt for around forty years and his rule is generally considered to have been a golden age. Amenhotep inherited a wealthy, powerful state (in part due to the military success of his grandfather, Tuthmosis III). He was not required to assert the strength of Egypt as none of her neighbours dared rise against her and so he was never really called to battle himself. There were a couple of minor military expeditions to Nubia, but nothing of great note.

The pharaohs of ancient Egypt had five royal names. His birth name (nomen) was Amenhotep Heqawaset (“Amun is Pleased, Ruler of Thebes) and his throne name (prenomen) was Nub-maat-re (“Lord of Truth is Re”). He also used the Horus name Kanakht Khaemmaat (“Strong Bull, Arising in Thebes”), the Nebty name Semenhepusegerehtawy (“One establishing laws, pacifying the two lands”) and the Golden Horus name Aakhepesh-husetiu (“Great of valour, smiting the Asiatics”).

Family

His father was the pharaoh Tuthmosis IV and his mother was Mutemwiya, the Great Royal Wife of Thuthmosis IV. She was generally considered to be the daughter of Artatama the king of the Mitanni (the allies of Egypt), but many now question this assumption.

Amenhotep III had a large harem, but he particularly favoured his Great Royal Wife Queen Tiy, who he married during the second year of his reign. Tiy was not of royal blood, but came from a family of powerful nobles. Her father, Yuya, was a powerful military leader and her brother, Anen, was Chancellor of Lower Egypt as well as holding the titles “Second Prophet of Amun”, “sem-priest of Heliopolis”, and “Divine Father”. Amenhotep III also married Gilukhepa, the daughter of Shuttarna II of Mitanni (in the tenth year of his reign) and Tadukhepa, the daughter of Tushratta of Mitanni (in the thirty-sixth year of his reign).

He had a number of children and it is thought that he intended for his eldest son, also named Thuthmosis, to succeed him. However, Thuthmosis junior died before his father and Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) was named as his heir. It is sometimes proposed that Amenhotep III was also the father of Smenkhare who ruled Egypt briefly after Akhenaten.

It is supposed that Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Isis, Nebetah and Beket-Aten were the daughters of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy. Sitamun, Isis and Henuttaneb are regularly depicted with their mother and father and Sitamun and Isis were both given the title “Great Wife” when they married their father. Nebetah only appears with her family once in a group of colossal limestone statues at Medinet Habu in which Amenhotep III and Tiy are depicted, along with Henuttaneb, Nebetah and another princess (whose name has been damaged). Beket-Aten appears in a relief on an Amarna Tomb which is generally dated to between year nine and twelve of the reign of his successor, Akhetaten.

Reign

Most scholars agree that Amenhotep III was only a child, between the ages of six and twelve, when he became pharaoh. A statue of the treasurer Sobekhotep holding the young prince Amenhotep-mer-khepseh is often thought to have been constructed just before the death of his father Tuthmosis IV, and the depiction of the young prince in the tomb of the royal nurse, Hekarnehhe, suggests that while he was still very young he was old enough to appear without his mother. It is likely that he was supported by a co-regent in the early years of his reign, but it is generally agreed that his mother did not perform this function. It is occasionally suggested that Yuya (the father of his Great Wife Tiy) may have held this role, as he was an experienced administrator from a powerful family.

New Kingdom pharaohs were expected to prove their military prowess to their subjects. However, there was little need for military strength during his reign. No-one dared mount a significant challenge to the might of Egypt at this time. There was a minor expedition into Nubia during the fifth year of his reign. Although this was recorded as a great triumph in inscriptions near Aswan and at Konosso in Nubia, it seems to have been little more than a brief trip south of the fifth cataract to remind the Nubians that he was boss. He boasts that he slaughtered many Nubians during a later rebellion at Ibhet, but it is thought that he did not actually attend the battle, instead leaving it in the capable hands of his son.

Amenhotep III celebrated three Heb Sed (jubilee) festivals, in years 30, 34, and 37 of his reign. He built a festival hall specifically for these celebrations in his Malkata palace which he named Per-Hay (“House of Rejoicing”). A clay docket from the Malkata palace suggests that Amenhotep III died in the 39th year of his rule (when he was perhaps only 45 years old).

Reign

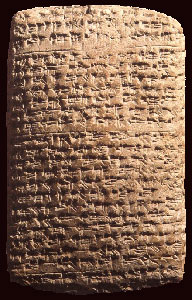

During the reign of Amenhotep III, Egypt began to export her culture and goods throughout the Mediterranean and the Near East. He was in regular correspondence with the Babylonians, the Mitanni and the Arzawa and foreign place names (particularly those of mainland Greece) began to appear in inscriptions with greater regularity. Examples of his diplomatic correspondence with the rulers of Assyria, Mitanni, Babylon, and Hatti was discovered in the archive of Amarna Letters.

The letters to Amenhotep III show that his neighbours made frequent requests for gold and other gifts (for example letters from Tushratta, King of Mitanni (EA17 and EA23) and the letters from Yabitiri the Governor of Joppa and Gaza). In one, (EA3 from Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon) the correspondence refers to Amenhotep’s refusal to offer one of his daughters as a bride. This refusal would certainly have been prudent as it could have given the foreign king (or his offspring by the Egyptian princess) a claim to the throne of Egypt, but it also indicates the standing of Egypt in the ancient world as the Babylonians were certainly not a weak power.

He sent at least one expedition to Punt to obtain precious incense and exotic plants and animals. The nobles of his rule certainly prospered, their lavish tombs attest to their opulent lifestyle.

Amenhotep III completed many ambitious building projects during his reign. In Karnak, he almost completely remodelled the temple of Amun dismantling the peristyle court in front of the Fourth Pylon and using the masonry as the filler for the new Third Pylon on the east-west axis creating a new entrance to the temple complex. He also constructed two rows of columns with open papyrus capitals in the centre of this new forecourt. He began building the Tenth Pylon at the south end of Karnak. This gateway led to a new entrance for the temple of the goddess Mut. There is also some evidence that he started building a new temple for this Goddess. In the north of Karnak, he built a shrine dedicated to Maat, and in the east he built a temple dedicated to the sun god.

Nearby, he extended the temple of Luxor building a new shrine to Amun Kamutef (“Amun, bull of his mother”) including a beautiful colonnaded court designed by the architect Amenhotep son of Hapu. At Sumenu, to the south of Thebes near Armant, he built a temple dedicated to Sobek. It is thought that this temple may have acted as home and breeding ground for sacred temple crocodiles.

He also expanded temples and shrines at Hebenu (the capital of the 16th nome of Upper Egypt) and (in the 15th nome of Upper Egypt) Hermopolis (dedicated to Thoth), at Memphis (where he built a temple to Ptah named “Nebmaatra United with Ptah”), at Elephantine, Elkab, Bubastis, Athribis, Letopolis, Heliopolis.

On the West Bank, across the water from Thebes he constructed his mortuary temple which was to become the largest of all of the royal temples. Unfortunately, it was built too close to the floodplains and by the Nineteenth Dynasty it was largely ruined and much of the masonry was recycled in other projects. All that remains are the famous “Colossi of Memnon” (as they were named by the Greeks). The West Bank was also the site of his Malkata palace. Although little remains of this palace, there is evidence that it was covered with beautiful paintings depicting scenes from nature. He also built a large harbour beside his palace. Further south along the West Bank, at Kom el-Samak, Amenhotep III built a painted mud brick Heb Sed (jubilee) pavilion

He built extensively (and extended existing buildings) in Nubia in Amada (dedicated to Amun) at Quban, Wadi es-Sebua, Sedinga, Soleb, Tabo Island, Aniba, Buhen, Mirgissa, Kawa and Gebel Barkal.

Religion

Amenhotep III was deified and was worshiped at his mortuary temple on the West Bank. However, unlike Ramesses II, no stele or statues so far recovered were specifically dedicated to Amenhotep III as a god during his lifetime.

He emphasised the solar aspects of a number of deities, such as Nekhbet, Amun, Thoth and Horus khenty-khem. Amenhotep III was certainly keen to promote solar religion and identified himself with the Aten. He often used the epithet Aten-tjehen (“the Dazzling Sun Disk” or “the sun disc gleams”). This title appears numerous times in the temple of Amun he built in Luxor and he often used a seal on which he claimed “Nebmaatra is the gleaming Aten” (Nebmaatra was his throne name). He also used the name Aten-tjehen for one of his palaces, a royal barge, and as the designation for one of the companies of soldiers in his army.

He also venerated (or feared) Sekhmet almost above all other deities. He placed an estimated six hundred statues of Sekhmet in the Temple of Mut, one seated and one standing version of the goddess for each day of the year. As the goddess most closely associated with the Eye of Ra and the fierce power of the sun it would seem that he had a particular interest in pacifying or appeasing her. It is also suggested by some that his devotion to Sekhmet was linked to his illness in later life. Priests of Sekhmet were often trained in medicine, and in particular surgery and she was thought to be able to cause or cure plague and pestilence.

Some scholars have suggested that when Akhenaten promoted the Aten, he may have been directly or indirectly promoting the worship of his father. It is certainly fair to say that Amenhotep III was associated with the Aten on his death, and he may have been considered to be the living incarnation of the Aten during the co-regency with Akhenaten that is proposed by some historians. Unfortunately, there is no firm evidence to support or contend the existence of a co-regency, and none to confirm whether Akhenaten was indeed raising his father above all the other gods of Egypt. It is interesting to note that while Akhenaten had the name of Amun removed from many of the statues of his father, he was always careful not to damage the images themselves, merely their connection with that god.

Art

The reign of Amenhotep III saw the creation of a huge number of sculptures and other art works and there is no doubt that his craftsmen were extremely highly skilled. In particular, many of the statues of the king are masterpieces. In fact, many of his statues are so beautiful that they were usurped by later kings. With over 250 of his statues having been discovered and identified, Amenhotep III remains the subject of more statues than any other pharaoh. There are also many beautiful examples of statuary featuring the women of the royal household.

Many noble families became very prosperous during his reign and so there was also a large increase in the number of statues created for private individuals and an increase in the number and quality of private tombs.

The reign of Amenhotep III is also notable as we have discovered a huge number of commemorative scarabs dated to that time. Over two hundred large scarabs have been recovered from as far away as Nubia and Syria. These scarabs commemorate events during the reign of the king and record his many accomplishments (some more fanciful than others).

Over one hundred scarabs record that Amenhotep III killed 102 (or possibly 110) lions with his own arrows during the first ten years of his reign. Another five record the arrival of princess Gilukhepa of the Mitanni, along with her maidservants. She later became one of his wives. Eleven record the creation of an artificial lake for his beloved Queen Tiy during the eleventh year of his reign.

Bibliography

- Bard, Kathryn (2008) An introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt

- Dodson, A and Hilton, D. (2004) The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt

- Hornung E (1999) History of Ancient Egypt

- Kemp B.J. (1991) Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization

- Van Dijk, Jacobus (2000) “The Amarna Period and later New Kingdom”, in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt Ed I. Shaw

- Rice, Michael (1999) Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (1999) A History of Ancient Egypt

copyright J Hill 2010