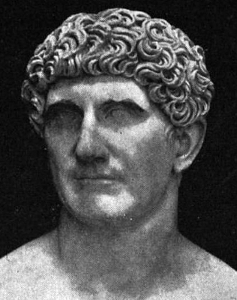

As noted in Cleopatra’s Early Life, it is possible that Cleopatra first met Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) when she accompanied her father (Ptolemy XII Auletes) to Ephesus to join forces with Gabinus, the subordinate of Julius Caesar. Mark Anthony returned to Egypt with Cleopatra and her father briefly and, even if she was not personally acquainted with him, she would certainly have been aware of his high esteem in the eyes of the people of Alexandria.

There is no doubt that they became allies during her stay in Rome when she was in a relationship with Julius Caesar and their friendship continued following his assassination. However, there had been rumours (probably encouraged by Cleopatra’s sister Arsinoe who was exiled in Ephesus) that Cleopatra had ordered the governor Serapion to give Cassius and Brutus a fleet which was moored at Cyprus during his war against Mark Antony and Octavian during the aftermath of the assassination of Julius Caesar. This is, of course, unlikely and a near contemporary source suggests that Serapion was acting unilaterally. However, Mark Antony (who needed Cleopatra’s financial assistance in his expansionist wars in the East) used these rumours as a pretext for summoning Cleopatra to Tarsus.

In 41 BC, despite her limited finances and the famine currently sweeping through Egypt, Cleopatra set out at the head of an ostentatiously equipped fleet to impress and seduce Antony. Knowing that he had recently declared himself the incarnation of Dionysius (who was often associated with Osiris in Egypt) she was dressed as Isis-Aphrodite (the consort of Dionysius). She may well have been wearing the famous pearl earrings retrieved from Mithridates (which were estimated to be worth 10 million sesterces each) in addition to other costly pieces of jewellery, and would certainly have been beautifully made up and manicured to make the most of her beauty. She also reputedly ordered that the opulent purple sails of her gold-prowed ship be drenched in perfume so that the divine scent would beguile the onlookers who lined the shore to witness her arrival (Cleopatra’s perfume was most likely a perfume based on Rose and Neroli) and her female attendants were dressed as Nereids (sea nymphs) and Graces.

When her ship finally docked a large crowd had assembled at the docks. Mark Antony sent a reception committee to her ship and waited in his pavilion, but Cleopatra never came. Eventually he realised that she was not going to come to him and he accepted her invitation to dine on board her ship. Then followed a series of lavish dinners using gold and jewel encrusted plates and goblets, all of which were given to Antony as a gift at the end of the feast. Cleopatra charmed him with her wit and vivacity and her wealth and regal connections appealed to his vanity and greed. In short, Cleopatra seems to have entirely captivated him.

Cleopatra then advised Mark Antony that it was in fact her sister Arsinoe who encouraged Serapion to give the Egyptian fleet to Cassius and Brutus (this may well be true) which made it an easy matter for Cleopatra to persuade Mark Antony to order Arsinoe’s execution. Unfortunately, Arsinoe was killed on the steps of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus causing further scandal in Rome. Cleopatra begged clemency for the priests of Artemis who were the guardians of Arsinoe, but extended no such request for Serapion or for a young pretender who claimed to be Ptolemy XIII raised from the dead.

Cleopatra must have been overjoyed to remove the last contenders for her throne and would have been delighted when Mark Antony announced that he was also giving her the territory of Cilicia. She announced her intention to return to Egypt and invited him to join her. After quelling a small rebellion in Syria he made for Alexandria where he received a jubilant welcome.

Mark Antony’s sojourn in Alexandria seems to have been a very happy one. He and Cleopatra were nearly inseparable and enjoyed feasting, gaming and hunting, and attended (and possibly even took part in) a series of plays. Rough seas made it impossible for Mark Antony to leave Egypt until the spring of 40BC, but it was generally rumoured around Rome that he stayed in Egypt because he was under the spell of Cleopatra. Reports of Mark Antony (and his friend Lucius) dressing up to take part in religious festivals and tales of lavish feasts and extravagant symposia at which great quantities of wine were consumed did nothing to improve his standing in Rome. Seneca remarked “Mark Antony was a great man, a man of distinguished ability; but what ruined him and drove him into foreign habits and un-Roman vices, if it was not drunkenness and – no less potent than wine – love of Cleopatra? “

Anthony had to return to Rome eventually and when he did the empire was split between the three generals (Antony, Octavian and Lepidus) with Antony taking control of the eastern territories as far as Albania. As part of the settlement Antony was married to Octavia, the sister of Octavian. This move most likely enraged Cleopatra, even if it seemed to be more of a political alliance than a love match, particularly as the following year (40 BC) she gave birth to twins, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II. The birth of mixed sex twins was particularly auspicious echoing Tefnut and Shu and Osiris and Isis and there was also the prophesy by the Sibylline Oracle that the Bull (Dionysius/Antony) would kill Capricorn (Octavian) and the virgin would change the fate of her twins in the constellation of the Ram (possibly a reference to Amun). Cleopatra’s astronomers were quick to interpret this as evidence that her offspring were destined to inherit Rome.

We can only imagine how Cleopatra felt when in 39BC Octavia and Antony had their first child (Antonia), or how she reacted when coins were struck to record the symbolic marriage between Antony and Athena Polias (patron goddess of Athens) and it was Octavia who was depicted as the goddess. Octavia seems to have been keen to supplant Cleopatra and she was certainly politically useful as she managed to keep the uneasy peace between her husband and brother for a time.

Octavia even persuaded Antony to give Octavian 130 ships in return for 20,000 troops to help Antony pursue his war against the Parthians. In 37 BC Antony set sail for the East accompanied by Octavia. She was pregnant with their second child and the journey was taking its toll on her, so she was sent back to Rome to the protection of her brother. It soon became apparent to Antony that Octavian had no intention of sending the troops he had promised and that in order to cement his hold on the East he would need the help of Cleopatra. Yet, in the four years they had been apart he had married another woman, fathered two children and he had never even laid eyes on his twins by Cleopatra.

In the winter of 37 BC Mark Anthony invited Cleopatra to join him in Antioch where they were married. Their reunion was no doubt emotionally charged but there were also political considerations prompting each party to forget the past few years’ separation and ignore the fact that Mark Anthony was already married to Octavia. We cannot know to what degree love was a factor in their decision to marry but we do know that Mark Anthony made generous grants of land to his new wife which amounted to almost all of the territory held by her dynasty at its height. On her triumphant march back to Egypt she stayed for a while in Jerusalem where her rivalry with Herod increased to the extent that he apparently planned her assassination. When Herod was persuaded that he would never get away with her murder he chose instead to impugn her character by claiming rather ineffectually that she had tried to seduce him.

By 36 BC she was back in Alexandria, a very wealthy and powerful woman. She elevated her first son, Caesarion, to full co-regent and her third child by Mark Anthony, Ptolemy Philadelphus, was born. Mark Anthony was not faring so well in Parthia. His allies had abandoned him and he was forced to retreat, losing a quarter of his men to illness and hunger. Octavia was sent to bring him supplies by her brother Octavian, but only 2,000 of the 20,000 men he had promised. Octavian knew that if Mark Anthony went to meet Octavia this would drive a wedge between him and Cleopatra, and if he did not go this would further distance him from Rome where his marriage to Cleopatra (which was illegal under Roman law) was unpopular.

Forced to choose, he picked Cleopatra and the relative freedom of the east sending Octavia back to her brother in Rome. When Mark Antony triumphed in Armenia the following year he chose to hold his triumph in Alexandria, not Rome (a move seen by some as implying that he intended to move his capital to Egypt). A celebration was held by Octavian in Rome without him, no doubt to underline his absence. Octavia was promoted to the status of Vestal Virgin and a modest statue of her (contrasting nicely with the opulent statue of Cleopatra placed by Julius Caesar) was set up beside one for Mark Anthony in the Forum.

During this triumph in Alexandria, Mark Antony proclaimed Cleopatra the “Queen of Queens” and claimed that he, not Octavian, was the adopted son of Caesar. He also formally pronounced Cleopatra and Caesarion the joint rulers of Egypt and Cyprus, Alexander Helios the ruler of Media, Armenia and Parthia; Cleopatra Selene II the ruler of Cyrenaica and Libya; and Ptolemy Philadelphus the ruler of Phoenicia, Syria, and Cilicia. In return Cleopatra paid to outfit a large fleet to help Antony wage war against the Parthians.

Antony’s frosty relationship with Octavian was now at breaking point and Octavian began a smear campaign to spread suspicion in Rome over the longer term plans of Antony and Cleopatra and to fuel the scandal over their marriage. As the war of words escalated Mark Anthony was accused of donating the spoils of his war to Isis not Rome and spurning his loyal Roman wife for a foreign whore, while Octavian was accused of homosexuality, cowardice and sacrilege.

Mark Anthony was not without friends in Rome and seemed to gain the upper hand when two of his supporters were made consuls. The true extent of his donations to Cleopatra (which were in fact confirmations of territory already agreed to enable Mark Anthony to govern the east) were disclosed to the Senate and Mark Anthony proposed to relinquish his powers if Octavian would do the same. Octavian responded with insults and threats even bringing an armed guard into the Senate! The two consuls and almost half of the Senate quit Rome to establish a new Senate in Ephesus where they were joined by Cleopatra (with a large fleet and plenty of gold) and a large army from the Greek nations. Mark Anthony and Cleopatra moved to Athens to prepare for hostilities and divorce proceedings were initiated against Octavia.

Octavian had to act but did not want to appear to start another civil war so focused on portraying Cleopatra as a foreign threat to Rome and an upstart female who wanted to “demolish the Capitol and topple the Empire”. Mark Antony was depicted as an emasculated traitor who was easily manipulated by a corrupt and debauched woman. His PR campaign began to work and in 32 BC Cleopatra was formally declared an enemy of Rome and a declaration of war made against her (in which Mark Anthony was not mentioned). The Roman fleet under the command of Agrippa met the two fleets of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium and Octavian was victorious. Dio recorded that Cleopatra beat a hasty retreat to Egypt, fearful that on receiving the news of their defeat officials of the court might try to depose her. Dio also claimed that she festooned garlands across the prow of her ship to suggest that she had been victorious and head off any would be conspirators.

Antony sailed to Pinarius Scarpus in Africa in search of allies and reinforcements but Scarpus refused to help him so he too fled to Alexandria. Dio also records that Cleopatra sent a golden sceptre and crown to Octavian signifying that she offered him the kingdom. Octavian responded by publicly threatening to seize her throne but secretly promised that if she killed Antony he would pardon her and allow her to retain her title. Antony attempted a short-lived defence of Alexandria but in the end he committed suicide rather than be taken back to Rome as a captive. He reportedly impaled himself on his sword and died in the arms of Cleopatra.

Cleopatra was captured and taken to Octavian who made it clear that he intended to take her back to Rome as a slave to be ritually executed at his triumph, but she deprived him of this pleasure by committing suicide before she could be transported to Rome. Caesarion was strangled, but her children by Antony were raised by Antony’s former wife, Octavia.

Bibliography

Classical Texts

- Cassius Dio (155 or 163 – post 229 AD) Roman History

- Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus aka Plutarch (c46 – 120 AD) Life of Antony

- Strabo (64 or 63 BC – AD 24) The Geography

- Flavius Josephus (c37 – 100 AD) Antiquities of the Jews

- Marcus Annaeus Lucanus aka Lucan (39 – 65 AD) Civil WarAppian (95 – 165 AD) Civil War

Modern Texts

- Joann Fletcher (2011) Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend

- Prudence J. Jones (2006) Cleopatra: a sourcebook

- Duane Roller (2011) Cleopatra: a biography

Copyright J Hill 2011