Hatshepsut (Hatchepsut) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and one of the few female rulers of Ancient Egypt. Her name means “Foremost of Noble Ladies”, and on her accession as pharaoh she took the throne name “Ma’atkare” (“Truth is the soul of Ra).

Family Background

Hatshepsut was the daughter of Pharaoh Thuthmosis Akheperkare (Thuthmosis I) and his great Wife Queen Ahmose. She had only one full sibling, her sister Akhbetneferu (Neferubity) who died in infancy.

Her father was also married to Mutnofret (possibly the daughter of Ahmose I) who bore four sons; Wadjmose, Amenose, Thuthmosis Akheperenre (Thuthmosis II), and Ramose. Both Wadjmose and Amenose died before adulthood. When her father died, her half brother Thuthmosis Akheperenre (Thuthmosis II) was named as pharaoh and she became his Great Wife. As descent was partially matrilineal, marrying Hatshepsut (the daughter of the king) supported the legitimacy of his rule despite the fact that his mother was not the Great Royal Wife.

Thuthmosis II ruled Egypt for either 3 or 13 years (the records are unclear). They had one daughter, named Neferure, who was often depicted wearing the royal false beard and the side lock of youth. Thuthmosis II also had a son named Thuthmosis who would later become Thuthmosis Menkheperre (Thuthmosis III) by a member of his harem named Isis.

When Thuthmosis II died, his son was too young to take power and so Hatshepsut was named as his regent and her daughter Neferure took on the role of the Queen in religious and civil rituals. Neferure became the wife of Thutmose III in order to confirm his right to rule (as his mother was not of noble blood). She may have been the mother of his eldest son, Amenemhat (who died before his father). However, this is not accepted by all scholars.

From Queen to Pharaoh

Her early career was not out of the ordinary. Many Queens had acted as regent to their infant sons, in particular Hatshepsut’s famous ancestors Ahmose Nefertari and Ahhotep. The role echoed the protection that Isis gave to her son Horus after the murder of Osiris and so was clearly acceptable to the gods. Hatshepsut was not Thuthmosis’ mother, but she was the daughter of the king, so had a better claim to regency than the mother of Thuthmosis. Hatshepsut’s actions as regent were also perfectly normal. Co-regencies were very common during the Middle Kingdom, as they avoided successional difficulties and allowed the junior pharaoh to be trained into his role. Hatshepsut fully acknowledged Tuthmosis III and made no attempt to take the throne from him.

A passage in the tomb of Ineni (a court official) notes …

He (Thuthmosis II) went forth to heaven in triumph, having mingled with the gods; His son (Thuthmosis III) stood in his place as king of the Two Lands, having become ruler upon the throne of the one who begat him. His sister the Divine Consort, Hatshepsut settled the affairs of the Two Lands by reason of her plans. Egypt was made to labour with bowed head for her, the excellent seed of the god, which came forth from him.

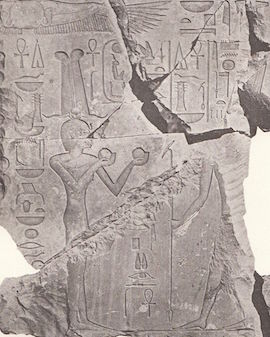

While still acting as regent, Hatshepsut was depicted at Karnak making offerings to the gods – usually the sole prerogative of the king. She uses the title “King of Upper and Lower Egypt”, “Mistress of the Two Lands, Maatkare” and wears a crown of two plumes and ram horns.

However, she also wears a long sheath dress and stands with her feet together (a female pose). This image is an uneasy compromise between the essentially male insignia and titles of kingship and her position as a female regent.

It is not clear exactly when Hatshepsut progressed from the role of co-regent to pharaoh, but it was sometime before or during her seventh year of rule because pottery jars with labels dating to that year were discovered in the tomb of Senenmut’s parents which name her as “The Good Goddess Maatkare”, the name she took as pharaoh.

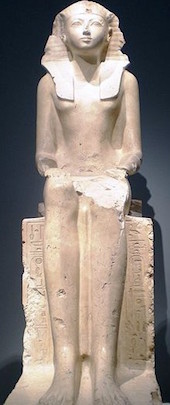

On becoming pharaoh Hatshepsut gradually assumed all of the symbols that went with the job including the Khat (a head scarf with an uraeus), the Nemes headdress, the shendyt kilt, and the traditional false beard. She occasionally amended her name to “Hatshepsu”, removing the feminine ending.

Yet, she was also occasionally depicted in feminine clothing and continued to refer to herself as a woman. As her reign progressed she was more often depicted as a traditional male pharaoh. She stopped using the titles of a Queen, in particular “God’s Wife of Amun. This was an important title first given to Queen Ahmose Nefertari and had a ritual significance. This title was passed to Neferure.

The unorthodox nature of this move required some justification, and a re-working of her history to play down her right to act as regent as the wife of Tuthmosis II and instead proclaim her right to be king as the child of Tuthmosis I. To achieve this, she skillfully employed art, architecture and inscriptions, notably by;

- Promoting the divine conception myth on her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri.

- Claiming that her father named her as his successor (in her mortuary temple).

- Claiming that she restored Egypt after the damage cause by the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period (in the temple of Pakhet at Beni Hassan).

She did not seek to exclude Tuthmosis III, or usurp his throne. He appears in all of her monuments except her tomb in the valley of the Kings. However, she is clearly the dominant party in the co-regency. In scenes where she appears with Tuthmosis III she is closer to the gods and usually strikes a more active pose.

Neither did she attempt to hide her own femininity, simply to adapt the iconography of a king to her own position. The female iconography did not allow her to be depicted as a ruler of equivalent or greater status than her co-regent, so she followed tradition and had herself depicted in the idealized form – as a male king.

She was a fairly conventional pharaoh in other respects. She is often described as a peace loving pharaoh, but this may be in part because of her gender. There were a few military expeditions but there seems to have been little dissent from Egypt’s neighbours (an indication that her rule was seen as strong).

She expanded the temple complex at Karnak, built her Mortuary Temple at Deir el Bahari and expanded Egypt’s trade (including conducting a famous trade mission to Punt). Hatshepsut died after a rule of twenty-two years and was buried with full honours beside her father in the Valley of the Kings. However, that was not the end of her story. Many years after her death her successor, Tuthmosis III, would make a concerted effort to erase her rule.

Pharaoh’s Names

Nomen; Ma’atkare

Copyright J Hill 2010