The Naqadan culture took over from the Badarian around 4500 BC and became arguably the most important prehistoric culture in Upper Egypt. It is named after the city of Naqada where much of the archaeological evidence for the period was found.

Naqada I

The early phase (Naqada 1, also called Amratian because of deposits found near the village of that name) ran in parallel to the Badarian culture, but slowly replaced it. They lived in small villages and developed the cultivation of the Nile valley, but the culture is most notable for the increase in artistic accomplishment and the proliferation of bearded male figures in addition to the female fertility figures.

Each village had its own animal deity which was associated with the clan of the villagers. This formed the basis of the nome system which divided Egypt into regions represented by their totems.

In Naqada I graves, the deceased were buried with statuettes to keep them company in the afterlife. These were the forerunners of ushabti figures found in Egyptian tombs. Along with these figures, the dead person was buried with food, weapons, amulets, ornaments and decorated vases and palettes.

Naqada II

The Naqada II (also known as Gerzean due to finds near the village of that name) phase began around 3500 BC. This culture mastered the art of agriculture and the use of artificial irrigation, and no longer needed to hunt for their food. The people built towns, not just villages, creating areas of higher population density than ever before.

The culture continued to develop artistic tendencies, creating new styles of pottery and more intricate carving. Many animal-shaped and shield-shaped palettes (used for mixing cosmetics) have been recovered. They form a clear link in development towards the ceremonial palettes of the early dynastic period (e.g. the Narmer palette). They also developed their skills in metalworking, in particular copper, which they traded with the ancient peoples of Mesopotamia and Asia.

The introduction of cylindrical seals (a typically Mesopotamian device) showed that their culture was influenced by their neighbours, but the familiar Egyptian gods Hathor, Ra, and Horus also date to this period.

Their burial rituals also changed. They created rectangular graves whose walls were lined with masonry or wood, and the body was not specifically oriented towards the setting sun. There was a marked difference in the quality of grave goods between the rich and poor and many contained pottery which had been ritually shattered during the funeral. Tomb 100 (The Painted Tomb) at Hierakonpolis is the earliest known decorated tomb, which was most likely the resting place of a local leader but may also have been reused and enhanced during the Naqada III phase.

Architecture also took a leap forward during the Naqada II period. A palace and ritual precinct was constructed in Nekhen (Hierakonpolis), which was the cult centre of Horus of Nekhem. It has a large oval courtyard, surrounded by small buildings, and is clearly the precursor to the ritual precincts of the Early Dynastic Period. Features of the complex (built of timber and matting) are echoed in the construction of Djoser’s step pyramid complex.

Naqada III

Naqada III (also known as “Semainean”) was a short period from 3200 to 3000 BC which is often referred to as the protodynastic period, or Dynasty 0. During this period there is a marked difference between the culture of Upper and Lower Egypt.

In Upper Egypt, an estimated thirteen kings reigned from Nekhen (Hierakonpolis). Unfortunately, only the last few have been identified. The kings were named after animals, no doubt relating to the favoured totem of their home towns. The ruler was seen as the personification of the god (in much the same way as later Pharaohs were considered to be the “Son of Ra”) and wore the white crown of Upper Egypt. The art work of the time suggests they were a fairly warlike bunch (for example the scorpion macehead, Narmer macehead, and Narmer Palette).

In Lower Egypt, the system was more bureaucratic and commercial. Important families ruled small areas and there does not appear to have been a rigid hierarchy. The rulers, such as they were, wore the red crown of Lower Egypt. Seven kings from Lower Egypt are listed on the Palermo stone. However, little is known about them and some doubt that they ever existed. Buto is generally considered to have been the largest and most important town, but there were also population centres at Ma’adi and Tell Farkha. Upper Egypt clearly influenced the art of the lower Egyptian peoples as almost all of the pottery found from this period was from Upper Egypt.

Horus and Nekhbet (the vulture goddess of Al Kab), came to represent Upper Egypt, while Set and Wadjet (the cobra goddess of Buto) represented Lower Egypt. The vulture and cobra were united to represent the pharaoh’s dominion over both lands.

Some scholars have suggested that the “followers of Horus” (led by Narmer or Hor Aha) defeated the “followers of Set” making Nekhem the most powerful town, and promoting Horus to the position of king of the gods. Thus, the pharaoh was the living Horus. Certainly the Narmer Palette shows the king wearing the crowns of upper and lower Egypt and includes an image of Horus dominating a personified marsh which is thought to represent Lower Egypt.

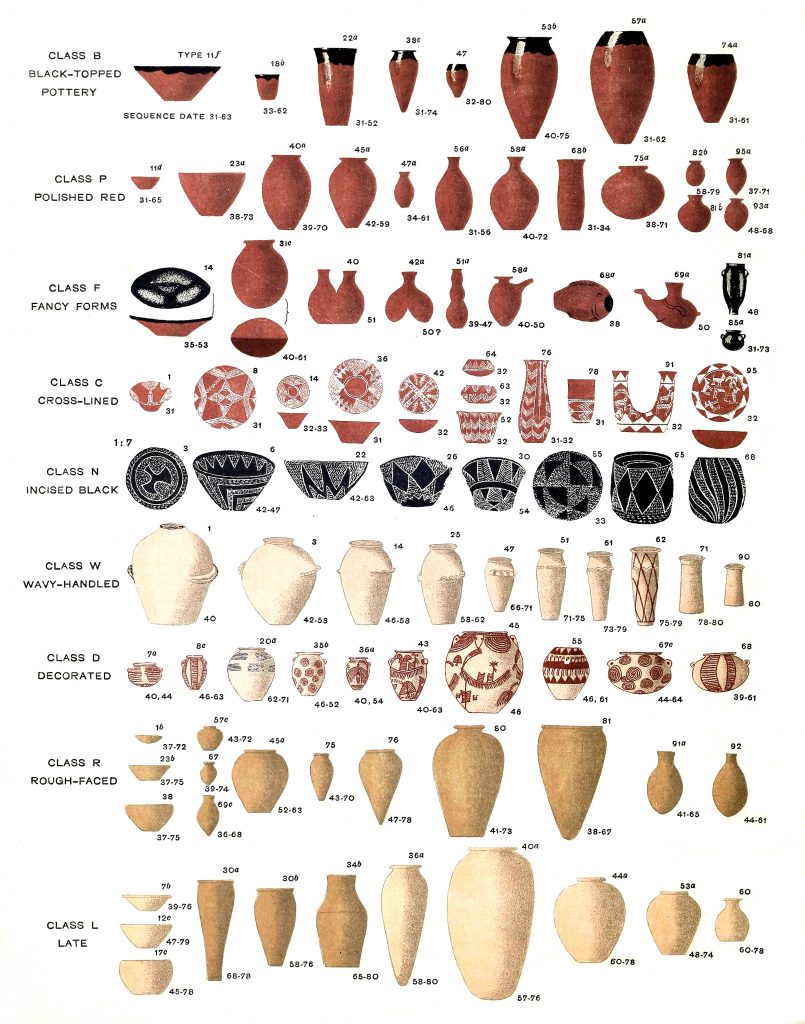

Pottery

Petrie developed a system known as sequence dating to chart the development of pottery styles over the Naqada period. He classified pottery based on the colours, styles and decorative elements in each piece and numbered them 30 – 80. 79 referred to pottery from the beginning of the first dynasty (Early Dynastic Period) and 0 – 30 were left free for earlier discoveries.

Bibliography

- Bard, Kathryn (2008) An introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt

- Brewer Douglas J. (2005) Ancient Egypt: Foundations of a Civilization

- Brewer Douglas J. (2012) The Archaeology of Ancient Egypt: Beyond Pharaohs

- Kemp, Barry J (1991) Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (1999) A History of Ancient Egypt

- “Prehistory”, S. Hendrickx and P. Vermeersch, “The Naqada Period”, B. Midant-reynes, and “The emergence of the Egyptian State” K. Bard in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (2000) Ed I. Shaw

- Wilkinson, Toby (2010) The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt

Copyright J Hill 2010