The Opening of the Mouth (“wepet-er”) was the most important part of the burial ritual. It transformed the deceased into an akh, the reanimated and effective spirit that was one of the elements of the ancient Egyptian concept of the soul. The first references to this ritual are from the Old Kingdom, and it remained part of their burial practices throughout Egyptian history.

When performed on a mummy it allowed the spirit of the deceased to see, speak, hear, breathe, and to receive offerings of food and drink. When conducted on a statue (or from the New Kingdom, a coffin), it allowed the statue to act as a surrogate for the body. Thus, the statue could act as a useful backup should the body of the deceased be damaged or destroyed. Many tombs included a statue of the deceased placed in a closed chamber known as a serdab. During the fourth dynasty of the Old Kingdom, only a bust of the tomb owner’s head was included!

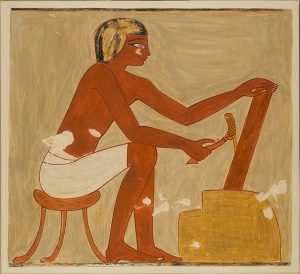

The ritual was conducted by the Sem Priest dressed in leopard skin robes. It could also be performed by the son of the deceased wearing leopard skin robes. In a royal burials, this may have been one way for the son of the king to confirm that he was the heir and successor of his father.

The ritual required the reading of numerous spells, and the sacrifice of a calf. Spells 21, 22 and 23 of the Book of the Dead refer specifically to this ritual. It also involved the use of a number of tools, including an arm shaped incense burner, a serpent headed blade, numerous amulets and the adze and peseskhaf.

The adze (a cutting tool similar to an ax) was also used for planing and carving in carpentry, boat building and house building. It was originally made of stone (particularly basalt and diorite), but in later periods often had a metal blade, sometimes formed from meteoric iron. The image of an adze was the hieroglyph for the word “stp” meaning chosen.

The peseshkaf was a spoon or fishtail shaped knife formed from a wide range of materials (including gold, carnelian, glass, obsidian, and flint). It was used during childbirth to cut the umbilical cord (one of the goddesses associated with childbirth, Meskhenet, was sometimes depicted with a peseskhaf on her head) and so in a funerary context it helped the deceased to be reborn. An amulet in the form of a pesheskhaf knife was often included in burial goods along with small jars of natron and resin (which were used in the preparation of the mummy).

During the funeral, the procession would make its way to the tomb. At the entrance to the tomb the Sem Priest would fall into a trance, and then be symbolically woken by the other priests. The sem Priest would announce; “I have seen my father in all his forms” and the other priests would respond by calling on the Sem Priest to take the place of Horus and protect his father Osiris (the deceased).

At this point the statues of the deceased would also be awoken so that they could receive offerings for the deceased. Then the lector priest would bring the foreleg of the sacrificed calf (which was similar in shape to the adze used in the ritual) to the mummy. This was thought to separate the ba from the body so that the ba could be free when the body was buried.

The Sem Priest would touch the face of the mummy with his finger, imitating the action of cleaning the mouth of a newborn infant, and offerings of grain and a peseskhef knife would be made to the mummy. The statue and mummy would again be purified and sometimes wrapped in a linen shroud, and a summary of the rituals recited. Finally, the mourners would enjoy a funeral meal, most likely involving the calf which had been sacrificed. The deceased, now reborn as an akh, could take part in this feast.

Bibliography

- Grajetzki, W (2003) Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt

- Ikram, Salima (1997) Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt

- Teeter, Emily (2011) Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt

Copyright J Hill 2016