The various royal emblems of the Ancient Egyptians often developed from fairly humble beginnings, but they became a powerful tool for expressing the duties and powers of the pharaoh, both graphically and symbolically.

Early versions of these emblems may have appeared crude and simplistic in form, or functional rather than ceremonial, but as time progressed royal emblems were formed from precious stones and other valuable materials and they were imbued with great cultural significance in this world, and also in the afterlife.

Scepters and Staffs

The sceptre or staff is one of the most ancient symbols of authority. The words “nobleman” and “official” both included the hieroglyph of a staff, so at an early stage the staff seems to have represented the authority of any person with significant power, not just the pharaoh.

One of the oldest staffs discovered in Egypt was recovered from a pre-dynastic grave in El Omari Lower Egypt (a neolithic site now absorbed by the suburbs of Cairo). We do not know whether the owner of this staff was a local chief, or priest, but it is generally agreed that the staff was an emblem of his authority. The staff soon became associated with pharaonic authority, but there were also forms which were solely associated with specific gods.

An early sceptre carved from wood to resemble a bundle of reeds was recovered from a First Dynasty mastaba in Saqqara. Similar fragments were found in royal tombs at Abydos and the pharaoh Den is depicted on an ivory label holding a long staff. A beautiful gold and sard ceremonial sceptre was recovered from the tomb of Khasekhemwy.

Was Sceptre

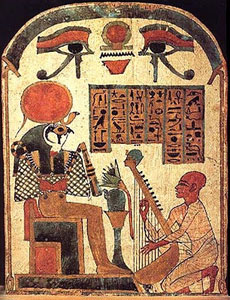

The Was Sceptre was a long straight staff with two prongs at the bottom and a canine head at the top. It symbolised power or dominion and was associated with the gods, as well as with the pharaoh. The earliest examples date to the First Dynasty.

An ivory comb from the reign of Djet depicts two Was sceptres supporting the outstretched wings of a falcon (representing the heavens). In a funerary context the Was Sceptre was also an amulet which ensured the well-being of the deceased and so often appeared as a decoration on funerary equipment. The sceptre also formed the hieroglyph for the fourth nome of Upper Egypt, whose capital was Thebes (known as Waset by the ancient Egyptians).

Mks Staff

The Mks (Mekes) Staff was a variant of the standard design of long staff, characterised by a nodule approximately half way down the staff. It is thought that it was originally a defensive weapon, used in conjunction with a mace, but soon accrued more ceremonial, priestly connotations. Stone vessels depict Anedjib bearing the mks sceptre, and Djoser is depicted with a similar sceptre on a panel located underneath the Step Pyramid of Djoser. The Mekes Staff was also used in the Great Offering ritual, together with the hedj club and the flail. There was also a shorter variant referred to as the Hts (Hetes) staff.

Heqa sceptre

The Heqa Sceptre (or shepherd’s crook) was closely associated with the king and was even used to write the word “ruler” and “rule” in hieroglyphics. It was essentially a long stick with a hooked handle and in later times it was often composed of alternating bands of blue and gold.

This sceptre became one of the most famous emblems of kingship. It is thought that the Heqa was originally associated with the god Andjety, who was himself considered to be a ruler. When Osiris absorbed Andjety, he also adopted the Heqa as one of his emblems.

One of the earliest examples was found in a tomb at Abydos (U-547) dated to the Naqada II period of pre-dynastic Egypt. This Heqa Sceptre was composed of limestone but was in fragments. Another early example (this time complete) made from ivory was found in the largest predynastic tomb in the Abydos cemetery (U-j).

The earliest representation of a pharaoh bearing the Heqa Staff is a statuette of Nynetjer, but arguably the most famous is that held by Tutankhamun in his sarcophagus. The Heqa was often paired with the flail, indicating that pharaoh was charged with the duty to guide the Egyptian people (represented by the Heqa) and his power to command them (represented by the flail). The Heqa was held by viceroys of Nubia or by the viziers (for example in depictions in the tomb of Tutankhamun).

Sekhem Scepter

The Sekhem Scepter was carried by gods, kings, and high officials. Deriving from the verb “to be mighty” it was also the logogram for the word “power”. Early dynastic kings were sometimes depicted with the Sekhem in their right hand and a censer or a mace in their left, while high officials usually carried the Sekhem on its own.

The Sekhem was closely connected with specific gods – most notably the goddess Sekhmet whose name (“the Powerful One”) was written using the Sekhem. Osiris and Anubis were both gods of the underworld who held the epithet “Great sekhem who dwells in the Thinite nome” and the Sekhem was part of the ritual observed in mortuary cults in the presentation of offerings to the ka of the deceased.

The Kherep Sceptre (“that which directs) and the Aba Scepter (“that which commands”) bear such a striking resemblance to the Sekhem that it can be difficult to distinguish them. However, they seem to have played different roles in the ceremonies, the Kherep being used by dignitaries and the Aba by commanders.

Flail

The flail (nekhakha) was a short rod with three beaded strands attached to its top. Its form was clearly ceremonial but probably derived from a shepherd’s whip. It may also have derived from the ladanisterion which is used to collect ladanum from the leaves of the cistus plant (or other gum bearing plants) which could then be used in the preparation of incense.

The flail was another popular emblem of pharaonic power. In early Egyptian history, it appears on its own (such as in the depictions of the pharaoh Den at his Sed festival on a label from the First Dynasty) but in later times if was often paired with the Heqa staff (or crook).

Like the Heqa, the flail was associated with the regal gods such as Andjety and Osiris. The flail was also associated with the ithyphallic deities, in particular Min, and was often depicted hovering above the hand raised above their head. The flail had associations with certain sacred animals (such as sacred bulls and hawks) who were often depicted carrying a flail on their backs. The flail was occasionally carried by priests or high officials, but this practice seems to have been limited to royal jubilee festivals.

Royal Mace

There seem to have been two forms of mace or club, the Ames (or Amesh) and the Hedj. Originally a functional weapon, over time it became primarily symbolic. It symbolised the might of the pharaoh, crushing his enemies, and was believed to confer invincibility on the bearer.

It was usually made of wood, alabaster, clay, or gold and great pride was taken in being the craftsman who made this sceptre. One of the titles recorded in the tomb of Prince Ramose is “Great Prophet of Heliopolis, unique one of festival, Craftsman of the Ames Scepter.”

Thutmose III claimed that “It was my mace which felled the Asiatics, it was my Ames scepter that struck the Nine Bows” (the traditional enemies of Egypt) and the mace is depicted in numerous “smiting” scenes. The Pyramid Texts in the pyramid of Unas pairs the Ames with the Lotus scepter to give dominion over the living and dead…

“Sit on the throne of Osiris, your Ames Scepter in your hand, so that you give orders to the living, your Lotus Scepter in your other hand, so that you give orders to those whose seats are hidden (the dead).”

Ureas

The ureaus was the image of a rearing cobra which was worn on the brow of the pharaoh, on top of a number of different crowns and headdresses. It was only worn by pharaohs, queens, and regal gods and clearly identifies royalty in art works and inscriptions. According to the Pyramid Texts, Geb granted the ureaus to the pharaoh as the legitimate ruler of Egypt. However, another (Ptolemaic) story tells that when Geb reached out to pick up the crown of Ra, so that he could assume the throne following the ascent to heaven of his father Shu, the ureaus attacked and almost killed him because it knew that he had committed a heinous crime by raping his mother Tefnut. This indicates that the ureaus was also seen as a protector of the law and punisher of the wicked.

The ureaus was closely associated with the cobra goddess Wadjet who was the patron of Lower Egypt and protected both the pharaoh and the queens of Egypt. Wadjet was also one of the goddesses associated with the Eye of Ra who could be seen as the personification of divine punishment and the protector of Ra in the underworld.

The ureaus was also a popular motif in architecture, statuary, and jewellery and was a commonly used hieroglyph (appearing in the name of Wadjet and the word “snake” and also in the names of other goddesses and terms for priestesses and shrines).

Bull’s Tail

The pharaoh was often depicted with a Bull’s tail hanging from the back of his kilt. It is likely that this emphasised the strength and procreative power of the ruler. This emblem was adopted at a very early stage in Egyptian history – it appears on both the Narmer palette and the Scorpion macehead (the Predynastic Period). In later periods, the bull’s tail fell out of favour, but epithets such as “Strong Bull,” or “Mighty Bull” were retained by many pharaohs.

False beard

Although beards were popular with ancient Egyptian men during the predynastic period, by the early dynastic period it had become fashionable, at least among the noble classes, to shave off all facial hair. This fashion spread to the rest of the population as time progressed. Despite this, certain types of beard were strongly associated with divinity – in particular, a closely plaited beard was considered to be a divine attribute. For this reason, the pharaoh would wear a ceremonial false beard in certain situations to emphasise his god-like qualities. This false beard was often made of goat’s hair and was wider at the bottom than the top.

When deceased, the pharaoh was often depicted as Osiris, and so wore the osiriform beard which was long and narrow with a curl at the end. Even non-royal men were sometimes depicted with a short form of this beard after their death.

Bibliography

- Allen, James P. (2010) Middle Egyptian

- Bard, Kathryn (2008) An introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt

- Kemp, Barry J (1991) Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation

- Wilkinson, Toby A H (1999) Early Dynastic Egypt

Copyright J Hill 2016