Sobekneferu (aka Neferusobek “the beauties of Sobek”) was the first attested female pharaoh of Egypt. She was the last ruler of the twelfth dynasty, towards the end of the Middle Kingdom.

Sobekneferu was the younger daughter of Amenemhat III. Her elder sister, Neferuptah, seems to have been groomed for rule before her. Unfortunately, she died before her father and the throne passed to Amenemhat IV. Manetho suggested that he was Sobekneferu’s half-sister and husband, but there is no independent evidence to back this up. She never used the title king’s wife, and neither did the mother of Amemenhat IV (Hetepi). In any case, when he died the throne passed to Sobekneferu.

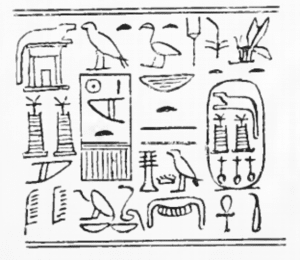

Her connection to Amenemhat III seems to be more certain, as she consistently associated herself with him on her monuments. Of particular interest is the depiction on granite columns of the serekh of Amenemhat III holding out the ankh (representing life) to the serekh of Sobekneferu. The implication is clear, she derived her legitimacy from Amenemhat. Some scholars have suggested that this may also represent a co-regency between the two rulers, presumably following the well attested coregency between Amemenhat III and Amenemhat IV.

There have also been some rather more speculative theories regarding a feud between Amemenhat IV and Sobekneferu, from which she emerged victorious. Again, there is no corroborating evidence of this. It has also been suggested that she was the pharaoh’s daughter who raised Moses. This imaginative theory is all too often supported by conjecture masquerading as fact and has not gained much support among Egyptologists.

The Turin canon gives her a reign of three years and ten months. During this time Sobekneferu extended the funerary complex of Amenemhat III at Hawara (called the Labyrinth by Herodotus) and undertook building works at Herakleopolis Magna.

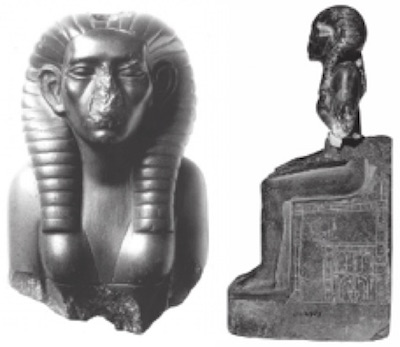

Much has been made of the images of Sobekneferu and her use of male clothing and regalia in her statuary. She generally used female suffixes on her titles, so there is certainly no reason to suggest she was trying to pretend to be male. However, in one fragment she was depicted wearing both a sheath dress and a male kilt. In another, she wears a sed festival cloak and a highly unusual crown which may be the result of an attempt to combine the crowns of a king and a queen.

Callender suggested that the ambiguity may have been an attempt to pacify critics of her rule, while Lloyd (rather speculatively) suggests they imply that her sex was an embarrassment! Graves-Brown, Tyldesley and Robins have persuasively argued that this should simply be seen as her desire to represent herself as a traditional pharaoh, which by necessity meant using certain male markers.

Her burial place has not been confirmed. It is often suggested that a badly damaged pyramid complex near that of Amemenhat IV at Mazghuna may be hers, but Dodson notes that there is no evidence to back this up. Perhaps her tomb may yet be discovered.

Pharaoh’s Names

- Manetho; Skemiophris

- Horus name: Merytre

- Nebty name: Sat-sekhem-nebettawy

- Golden Falcon name: Djed-et-kha

- Prenomen: Sobekkare

- Nomen: Sobeknefru

Bibliography

- Capel, Anne K and Markoe Glenn E. (Editors) (1996) Mistress of the House, Misteress of Heaven

- Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan (2004) The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt

- Fay, Biri et al (2015) “The Neferusobek Project, Part 1” from The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1550 BC) Edited Miniaci, Grajetzki pp 89-91Graves-Brown, Carolyn (2010) Dancing for Hathor

- Hawass, Zahi (1995) Silent Images: Women in ancient Egypt

- Robins, Gae (1993) Women in Ancient Egypt

- Shaw, Ian (Editor) (2000) The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt

- Troy, Lana (1986) Patterns of queenship in ancient Egyptian myth and history

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2006) Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt

- iegler, Christine (Editor) (2008) Queens of Egypt: From Hetepheres to Cleopatra

Copyright J Hill 2018